Early-life stress causes “sex change” as males rewire their brains and behaviour

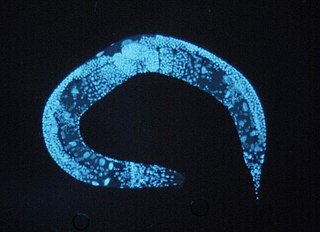

Temporary starvation during early life can result in adult brain connectivity, gene expression and behaviour that resemble the other sex; at least for male nematode worms (C. elegans), that is.

Across the animal kingdom, male and female brains differ in their development, from the molecular to behavioural levels. Early-life stress can have differential effects on the cognitive and behavioural capacities of males and females that persist into adulthood. However, proving that sex-specific changes at the molecular level caused by early-life stressors drive differences in later behaviour has been challenging.

Using detailed molecular and genetic investigations in C. elegans, Emily Bayer and Oliver Hobert from Columbia University in New York have addressed this challenge by revealing how early stress differentially affects maturation in the two sexes, male and hermaphrodite, to remodel neuronal circuits and change adult behaviour. During normal development, each sex undergoes a precise pattern of synaptic pruning in a set of neurons common to both sexes, which is crucial for later sex-specific behaviours, such as the male seeking hermaphrodite mating partners.

However, Bayer and Hobert found that C. elegans males starved at an early stage of development did not show the expected pattern of pruning in phasmid neurons, which allow the worm to respond to chemicals in the environment. Instead, starved males retained synaptic connections in adulthood which are normally only present in adult hermaphrodites; in contrast, starved hermaphrodites showed normal adult synaptic connectivity patterns. This synaptic “sex change” in males also modified adult behaviours, enabling them to avoid chemicals normally only sensed by hermaphrodites, but also impairing their mating behaviour.

" early-life starvation resulted in a lifelong “memory” of the stress ... disrupting sex-specific synaptic pruning "

Applying the power of C. elegans as a model system, the authors investigated the precise molecular signals and neuronal classes responsible for the starvation-induced “sex change”. Their investigations revealed that RIC neurons signal starvation using the neurotransmitter octopamine, while ADF neurons signal satiety using serotonin. Increased octopamine release from RIC neurons during early-life starvation resulted in a lifelong “memory” of the stress in ADF neurons, manifesting as a permanent reduction in their serotonin release. This in turn was responsible for disrupting sex-specific synaptic pruning in phasmid neurons, solving the mystery of how molecular signals for starvation resulted in changes to later behaviour in the worms.

...

These findings provide a detailed picture of how early-life stress and sexual maturation interact to affect brain development and behaviour, an interaction which is likely important across the animal kingdom.

Cover image: GerryShaw (Wikimedia)

← Back to portfolio